Between slow and sudden death in Turkey

The Committee for Human Rights is proud to host this article contributed by colleagues from Turkey and Turkish Kurdistan. The authors of this piece are signatories of the Peace Petition and preferred their names to remain anonymous. The opinions expressed in this piece are the authors’ own and do not reflect the view of the Academics for Peace.

Between slow and sudden death in Turkey

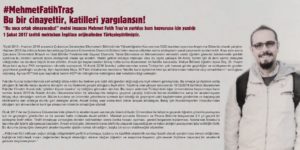

On February 25, 2017, the picture of a young male academic who committed suicide in Turkey went viral on the social media. The photo was hashtagged with #MehmetFatihTras and the line underneath the hashtag reads: “This is a murder. Try the murderers!” Wearing hipster eyeglasses, a hooded jacket, and a bag pack, Mehmet Fatih Tras has recently completed his doctorate degree in Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences at Cukurova University in Turkey. Upon the receipt of his Ph.D., he was made multiple job offers from universities in Turkey. However, university presidents interrupted the recruitment process and terminated his contract without any justification. His last job letter submitted to an international academic institution is a testament to what this young academic had gone through. “I was blacklisted by the Council of Higher Education,” he said, “university presidents labelled me as terrorist.” Tras was one of 1,128 academics from 89 universities in Turkey who had signed a petition condemning state violence in the Kurdish region of Turkey.

Figure 1: The letter Mehmet Fatih Tras wrote to an international academic institution on February 1, 2017 circulated on the social media with his picture on the right.

The petition, famously known as “Peace Petition,” was prepared by the Academics for Peace on January 11, 2016 when the Turkish Army besieged Kurdish towns of Sur, Silvan, Nusaybin, Cizre and Silopi, and announced round-the-clock curfews which functioned as indefinite military lockdowns. “It [the army] has attacked these settlements with heavy weapons and equipment [tanks, artilleries, snipers] that would only be mobilized in wartime” the petition noted. Signatories defined these military operations- called the Cleansing Operations by the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) government- as “a deliberate and planned massacre”, and demanded the state to stop military operations, lift curfews, punish those responsible for human rights violations, offer compensation, and resume peace talks with the Kurdish movement. After listing their demands, signatories asserted their strong opposition: “We, as academics and researchers working on and/or in Turkey, declare that we will not be a party to this massacre by remaining silent.”

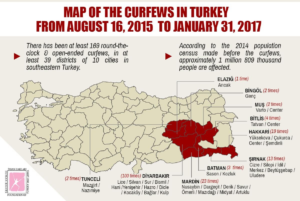

Because of the total lockdown, the extent of state violence was unknown by the time this petition was written. Within less than three months, however, we would learn, for example, that around 200 civilians were killed in Cizre. A report published by the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey (TIHV), in August 2016, identifies by name 321 local residents who were killed between 16 August 2015 and 16 August 2016, including 79 children, 71 women and 30 people over the age of 60. According to the report, during the 79-days-long military lockdown, 10 thousand homes were destroyed. Cizre was not an exception though. Sur was under military blockage for 103 days during when 90 civilians were killed. 6,297 parcels of Sur district, which was destroyed by the Army, would then be expropriated by the AKP government. According to TIHV, there have been at least 169 round-the-clock and open-ended curfews in at least 39 districts of 10 cities in the Kurdish region from August 16, 2015 to January 31, 2017. TIHV estimates that more than 1 million 809 hundred people were affected during this period (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: http://tihv.org.tr/16-agustos-2015-31-ocak-2017-tarihleri-arasinda-sokaga-cikma-yasaklari/ (accessed 3/2/2017)

The gravity of the destruction became more evident with the Report on the human rights situation in South-East Turkey (July 2015 to December 2016) released by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR) on March 10, 2017, which reported the killing of 1,200 civilians and documented “numerous cases of excessive use of force; enforced disappearances; torture; destruction of housing and cultural heritage; incitement to hatred; prevention of access to emergency medical care, food, water and livelihoods; violence against women; and severe curtailment of the right to freedom of opinion and expression as well as political participation. The most serious human rights violations reportedly occurred during periods of curfew, when entire residential areas were cut off and movement restricted around-the-clock for several days at a time.”

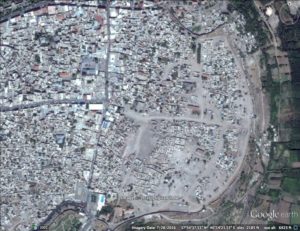

Dr. Tras and 1,128 other academics declared that they would not be a party to this crime when the massacre was in the making. The government did not allow any international or local institutions to monitor or report the incidents at the time. On the contrary, it banned civilian access to curfew sites both during and after the Cleansing Operations. Some curfew sites have recently been opened to civilians only after bulldozers razed the remaining buildings to the ground, removed the rubbles, and, thus eliminated any possibility for fact-finding. In its account of the situation, the AKP government resorts to the same state discourse- the “terrorists” destroyed houses, killed civilians, and displaced millions. The burden of proof lies on the shoulders of the Kurds who return home only to find a flat field in the place of their houses (compare Figure 3 and Figure 4).

No petition could end a war. It might make its signatories feel good about their politics and ethics for a second. On the next day, the life, supposedly, goes on as usual and so does the war. In the face of state denialism and censure, however, the Peace Petition had the potential to destabilize the hegemonic discourse of “terrorist” violence. It was the first time that academics collectively used their privilege to speak to expose the unfolding state massacre in the Kurdish region of Turkey as well as the violence of its defacement. Therefore, the life did not go on as usual on the next day. Instead, the President Erdogan appeared on televisions ostracizing the signatories by calling them fake and shady. “Turkey faces treason of academics,” Erdogan claimed and added “most of whom receive their salaries from the state.” He ordered public prosecutors and university presidents to start criminal and administrative investigations against those “traitors.”

As a result of this smear campaign, 312 signatories of the petition have lost their jobs in the last 14 months. Others have been suspended from their positions, charged with terrorist propaganda and detained by the police, received life threats, and/or fled the country. The already precarious labor market for academics has become even more precarious as the value of academic labor is determined by the level of loyalty academics express to the state. Those speaking back to the state have been replaced by academics speaking for the state. In other words, Turkish academia has turned into a deserted platform more akin to government mouthpiece where criticism and opposition are susceptible to accusations of terrorism. The academics that regard speaking up both as a matter of political and ethical responsibility, end up with two options: either remain silent or become traditional intellectuals of the state.

This is an alarming situation with respect to not only the right to speak but also the right to life. The Peace Petition has derived its power from tying these two rights tightly to each other by asserting that silence means complicity in state massacres. From a Foucaultian perspective, signatories acted as the parrhesiastes – the one who says the truth despite the risks involved in its disclosure. By doing so, they have also tied their fate with the ones subjected to the cruel violence of the state. While the Kurds in Turkey experience sudden death exerted by the latest offensive of the Turkish Army, academics who spoke up against it face slow death by the market. Mehmet Fatih Tras’s grim departure discloses the entanglement of our lives as well as our deaths. Ironically, on the same day when his picture was shared on the social media, another hashtag was created with the name of a village, Xerabe Bava, in Nusaybin, which was under military lockdown for 19 days. It is more urgent than ever to reconnect #MehmetFatihTras and #XerabeBava to fight against deadly forces of the market and the state that turn our lives into slow or sudden deaths.

Note: The authors of this piece are signatories of the Peace Petition and preferred their names remain anonymous. The opinions expressed in this piece are the authors’ own and do not reflect the view of the Academics for Peace.

Filed under: academic freedom, anthropology, Human Rights